Is Teaching Patriotism Possible?

Lisa Noël Babbage

Author, Teacher, Philanthropist

Aug. 1, 2018

“When we spend all of our focus on what we do not agree on, we do not focus on the things we do agree on; and that's anti-patriotic.”

The question as to whether or not public schools should teach patriotism is still debatable in certain sectors. To what degree teaching this subject matter is Constitutional and how can successful patriotism be taught are undetermined algorithms. It’s difficult enough in some neighborhoods to teach multiplication, which has an assigned, undisputed set of factors and protocols. In light of all of the absenting opinions, patriotism is not as clear cut.

In 1828, patriotism was defined as “Love of one’s country; the passion which aims to serve one’s country, either in defending it from invasion, or protecting its rights and maintaining its laws and institutions in vigor and purity. Patriotism is the characteristic of a good citizen, the noblest passion that animates a man in the character of a citizen.” By today’s definition, less than two hundred years later, patriotism is simply coined as “devoted love, support, and defense of one’s country; national loyalty.” Does the reduction in words come as a result of the fast paced society we now find ourselves in, or is there more to it?

The fact of it is that people define patriotism differently. What is patriotic to one person is offensive to another. The meaning behind the words we use give listeners untold number of skepticism and doubt because we have come to accept truth as being progressive, not abstract. When truth changes based on the circumstances happening at any given time, how can one clearly identify what is or is not patriotic. That is why it is so difficult for public school teachers to go deep when it comes to teaching patriotism.

With students all over the country returning to classrooms, it’s time to find out exactly where we stand. The real truth is that when we spend all of our focus on what we do not agree on, we do not focus on the things we do agree on; and that’s anti-patriotic.

Public schools were designed to teach immigrants pouring into this country how to be successful Americana, among other things. Horace Mann, as Secretary of Education, proposed a standard curriculum to the Massachusetts assembly which was eventually adopted by other states. This standard curriculum was set up to reduce the disparages between the wealthy, who were able to hire teachers to education their children, and the impoverished, who were functionally illiterate in many cases. Patriotism was one of the subjects early American schools promoted. They did so not just to unify the young nation, but to help perpetuate what the nation was founded on.

The influx of other cultures were to add to the definition of ‘America,’ not detract from it. Public school ensured this notion of national identity from a very early point in American history.

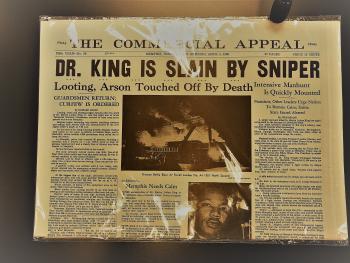

In fact, since the early public schools, the government debated on whether or not tax payers should pick up where parents left off and to what degree. Education reforms during the civil rights era, for example, officially ended segregation in the United States. This was considered a national priority when public outcry to adhere to the Constitution’s definition of citizenship won out over prejudice. The Convention Against Discrimination in Education was adopted by UNESCO in 1960 and went on to combat religious, racial, and other discrimination in public education. This was enforced so that public education protected what was constitutionally mandated. In the 1970’s and 80’s, the topic of sex education was being debated. What part was the parent’s obligation and what was society’s obligation came before Congress and the American public. What once only taught social hygiene was now to include more explicit information regarding sexually transmitted disease and unplanned pregnancy. In the early 1990’s, public education evaluated the way students with disabilities were being accommodated in the average classroom. This outcry and investigation led to legislation protecting the rights of disabled Americans to benefit from free access to education. The bottom line is that public education and family values have been intertwined since the entity’s inception.

Our post 9⁄11 world experienced a resurgence in patriotism. However, the practice of teaching our national identity has fallen behind the needs of worthy special interests that had not been specifically addressed when mandatory schooling was initiated. So now, as patriotism has been called on the proverbial carpet of our evening news, how do we promote what has historically been a cultural necessity?

The establishment of Constitution Day or Citizenship Day (September 17th) as a non-federal holiday in 1787 was added to the Congressional record in 1941 when Hungarian immigrant Clara Vajda sparked the idea to teach all citizens to appreciate the honor national sovereignty afford them. The Speaker of the House, Thad Wasielewski of Wisconsin, reported that the charity of a foreign-born citizen is ultimately responsible for the Act that should have embed the teaching of patriotism in every public school classroom.

Neither Vajda or Wasielewski had an inkling that the world would be discussing topics like gender more than we are our own national identities. Patriotism is no so easily defined nowadays because many Americans choose to self-identify by their special interests above their citizenship. Occupations, sexual orientation, ethnicity, even religion, can separate us from what it used to mean to be patriotic when we only focus on difference. As Americans, we have to remember that it is our embraced differences that make us Americans, those differences we do not embrace destroy what it means to be American.

For educators welcoming a new class this month, teaching patriotism may have to be factored into what it means to teach embracing difference. Because if we make a decision to recognize and embrace difference, we can actually see we have more in common as Americans than we have incongruous. To illustrate it physically, when we literally embrace someone or something, we completely blur the line that separates us from that person or thing. We become one. Now that’s a patriotic idea.